Entertaining finds

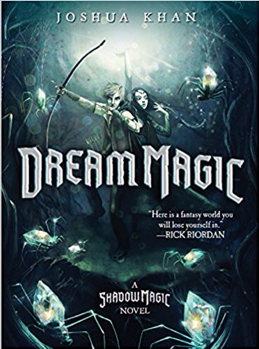

Here are two great finds for children's fantasy. They are wonderful books. And these ones really are for children (US 'Middle Grade'); so many 'high' fantasies stray into Young Adult territory. UK readers may need to seek them out though. Despite their London-based author, they don't seem to be too widely known here yet. They are, however, very successfully published in splendid editions in the US.

I am generally very sceptical indeed of book blurb which offers a successor to Harry Potter. But although these magic fantasies are quite different from J K Rowling's stories, I do agree that they will have something of the same appeal to much the same audience. They are hugely entertaining, completely enthralling, exciting and endearing in equal measure. ,

Fantasy with a twist

They have many of the classic ingredients of high fantasy, small warring kingdoms of a broadly 'medieval' nature, scorcerers and warriors, lords, princes and princesses, fantastic beasts (occasionally doubling as magical pets), a displaced waif adopted as an 'apprentice', evil plots and even more dastardly villains. The main twist this author brings is that Lily, one of the very likeable young protagonists, is heiress to a kingdom of dark sorcery, rather than the usual champion of 'the light'. This gives plenty of scope for a world of wicked magic, zombies, bats, crumbling, haunted castles and the like, although, as appropriate for the young audience, it all has rather more in common with Disney or the Adams Family than with Denis Wheatlley and the occult. It is the source of as much humour as horror. However, even though she is now ruler of Gehenna, following the recent murder of her parents, Lily is forbidden from learning sorcery because of being female. However, feisty young thing that she is, you can't see her abiding with that rule for too long.

Lily is complemented by a young male character, Thorn, rescued from slavery by the kingdom's 'Executioner', Tybirn, and brought to her court, for motives only much later to become apparent. Thorn is a down-to-earth, likeable lad, and their unexpected developing friendship is one of the book's many joys. A trio of young protagonists is completed by K'leef, a poor little rich boy (with a magic of his own) who is currently being held hostage from a neighbouring kingdom. Together they make as utterly charming a cast of 'heroes' as I have found in this type of story for a long time. Then there is the 'pompous, arrogant, bullying and entirely moronic' prince from the neighbouring kingdom, who Lily is supposed to marry to cement a peace treaty Well, feisty young thing that she is . . . Enough said I think.

And a mystery too

Around these young people and their engaging world, Joshua Khan weaves a zestful, rumbustious tale that constantly trills, delights, and terrifies. As Lily herself in some senses represents 'the dark' , this cannot be the usual high fantasy plot to overthrow the powers of darkness, instead this first book is more of a murder mystery. It is something of a who-done-it in terms of the killing of Lily's parents, an attempt to poison Lilly herself, and other equally dastardly deeds. As an adult reader, I actually cottoned on quite quickly to where the plot was leading. But I don't think many younger readers will. To them, the final revelation will come as a surprising and indeed a shocking one.

Together with the theme of Lily asserting herself as a girl (quite right too) and Thorn and K'leef finding something of their role in life, this is just about as rich and rewarding a read as most children could wish for. Oh, and did I say entertaining, exciting, enthralling and endearing? I surely should have.

Strong sequel

Second books in a series can sometimes feel a bit of a disappointment, a rather pale repeat of the first. However, here, Joshua Khan cleverly exploits the potential without falling into any of the bear traps. His young protagonists are already beginning to feel like old friends, but he continues to develop their characters and relationships well. Similarly, he succeeds in developing his world, giving readers more of what they enjoyed so much the first time around but without the storyline feeling in any serious way repetitive or predictable. In fact I found even more humour in this book and the darkness has become even darker, more ghoulish, although, still never seriously disturbing.

In this episode, Lily, our young ruler of the Dark Kingdom continues to develop her (forbidden) powers as a sorcerer. As a consequence she has 'let through' countless undesirables, zombies and worse. Worse than zombies? On yes. Believe me. Far worse. She still needs her friendship with loyal commoner, Thorn, very badly.

This story too is bursting with shocking incident and exciting action. It is an unrelenting and involving page-turner, a delightfully entertaining read throughout and exactly the sort of book that will engage and delight countless young readers, as well as hooking in many potentially more reluctant others. If it is not quite Harry Potter (what could be?), then it is probably as good a substitute as those with no Hogwarts left are likely to find.

Seek them out

Which makes it altogether mystifying why these hugely entertaining young reads, by a London-based writer, are very successfully published in the US but don't as yet seem to be so widely known over here.

It sometimes feels to me that there might be a degree of prejudice around against full-blown fantasy and in favour of books that deal with 'real life', with 'issues'.

If so it is seriously misplaced. Of course 'real life' books have a vital place in the children's canon. However, fantasy is an exploration of imagination, and that is just as much a part of our human make up as our ability to cope with the everyday. Fantasy nurtures and expands the imagination and imagination is the core of all the Arts, as well as of many other fields of endeavour. Indeed it is the essence of all creativity. And much fantasy does in fact deal with profound human issues too;it is just that it does it through metaphor, through distanced narrative, rather than facing them head on. It still leads to learning through vicarious experience. It is just that that experience is dressed in images.

All story is powerful. All story is fundamental We should beware of valuing some of its manifestation more than others. It can lead to an imposition of our own ideas of what is correct, what is best, over the breadth and depth of provision which allows children to discover for themselves what it is that they want and need.

And do we require anything more than young Potter to demonstrate both the potency and popularity of fantasy for huge numbers of young readers, here in the UK as well as in The States?

The good news is that #3 in Joshua Khan's trilogy, Burning Magic, is due out next Spring, over there at least. Oh, and by he way, the splendidly handsome US hardbacks are considerable enhanced by Ben Hobson's striking illustrations.