'The wound is the place

Where the light enters you.' (P 307)

I have just discovered two more wonderful books.

Those who have read this blog before will know how highly I value originality of imagination in children's fantasy, especially when paired with skilful writing. I certainly found both here.

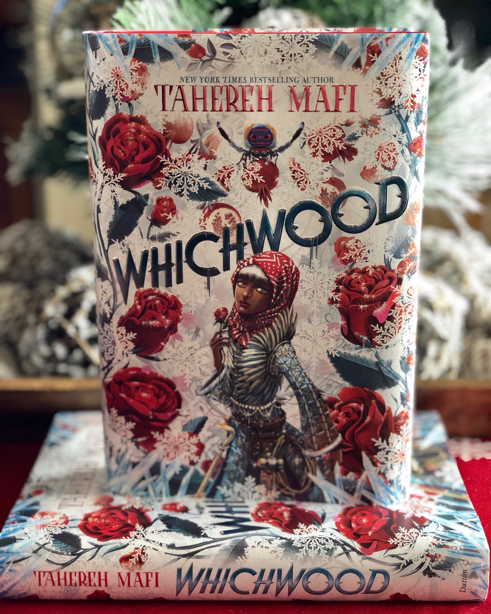

The very recently (US) published Whichwood is actually the second in a series. So, as I haven't posted anything about the first yet, it makes sense to start with that.

'People are so preoccupied with making sense despite it being the most uninteresting thing to manufacture. Making magic is far more interesting than making sense.' (p 168)

Glowing colours

The core plot of Furthermore may not, in itself, seem startlingly new. A girl from a magical community fails her coming-of-age trial (or thinks she does). She is subsequently whisked off with a boy companion to an even stranger fantasy world in quest of her long-missing father. However, any suspicions of staleness are swiftly and thoroughly dispelled by Tahereh Mafi's wholly original and sparklingly imagination. Her creation of a world where magic is related to colour glows in every possible way. Her inventions are wild, wacky and completely enchanting. Furthermore (sorry!), her whole story is anchored in one of the most entertaining character relationships of recent children's fantasy. Protagonist, Alice, and her counterpart, Oliver, are not only totally fascinating in their own right - complex and flawed, whilst still being immensely likeable - but their continually developing relationship is an ongoing joy. That may start off by bickering like Beatrice and Benedict but . . . well, no spoilers.

Sparkling words

Additionally, Tahereh Mafi's highly skilled use of language is often idiosyncratic in the most delightful way. It surprises on almost every page and this gives the book a thrilling liveliness. She endows Alice's home world with its own word-hoard of coined language, exotic-sounding yet still comprehensible in its context. This gives Ferenwood, and Alice's life there, a vividness that is completely captivating. A further writerly frisson is added when the narrator (author?) periodically intrudes into her own story. She belongs to the time-honoured 'dear reader' school, of narration, colouring (sorry again!) both text and section headings with a delicious and highly entertaining soupçon of meta fiction.

Riotous magic

The place to which Alice and Oliver travel to seek Alice's father is the Furthermore of the title. Here magic is used profusely, even with profligacy. Its world is a riot of weirdly imaginative invention, like that of Lewis Caroll, bursting with conceits and cleverness, linguistic. literary and logical (or illogical). However, also like the Wonderland of that other Alice, its continual irrationality generates a certain randomness. The protagonists' stumbling from one catastrophic 'adventure' to the next could seem haphazard. Yet in Tahereh Malfi's hands the through line of narrative is fully sustained: she cleverly engenders a continual fascination with the two heros and their quest. Despite all the seemingly random oddness of Furthermore, the reader is propelled forward by what is the very essence of good storytelling, the desire to discover exactly what is going on, to find out what happens next.

A ribbon runs through it

There have been many children's novels recently with strong, feisty girl protagonists. Many other books are showing how girls and women have been high achievers in any number of ways. These role models are so important. However Furthermore captures something that I think is important too: a girl who feels inadequate compared to what she sees as all the more obviously talented people around her. It is not just about being strong and successful in the way others are. It is about learning to see the strength in who you are.

'Darling Alice,' said (her father), reaching for her, 'Why must you look like the rest of us? Why do you have to be the one to change? Change the way we see. Don't change the way you are. . . You're an artist. You can paint the world with the colours inside you.' (p 254)

It is, at the end of the day, a book that revels in the joy of language. It celebrates imagination - and, well, magic. It encourages openness to experience. It promotes difference and extraordinariness and adventure. It is also a compassionate book which gives permission for girls (or boys for that matter) to sometimes be weak as well as strong. And I think that is something we all need.

'(Alice had) decided long ago that life was a long journey. She would be strong and she would be weak, and both would be okay.' (p 255)

Altogether it is a triumph of original and captivating children's fantasy. It is a dream; it is a poem; it is a painting. It very special and its final messages are amongst the simplest, most difficult and most important in life.

Through this magical book, in between its chapters, dances a ribbon. But you must follow it for yourself.

'the strangest sort of children come to hold hands with the Dark.' (p 41)

Writing an immediate follow-up to a highly successful opener can be a challenge, and many a second book is a little disappointing, even some of those within outstanding sequences. Yet in Whichwood Taharah Mafi far exceeds even her own previous success. She does not try simply to produce more of the same, but takes her tale in a completely fresh direction (and to a radically different world), whilst still maintaining continuity by bringing forward her two protagonists, Alice and Oliver. Additionally, she not only reproduces her most exciting qualities as a writer, but develops them wonderfully too.

Colours just as rich, but darker

The fantasy world she builds here is every bit as original, imaginative and colourful as Furthermore. However, lacking the random, Wonderland quality of that previous location, Whichwood it is far more consistent in its ethos and atmosphere. In consequence, this story seems far more coherent and even more compelling. It is considerably darker too, disquieting, even at times disturbing. (I know our heros were under threat of being eaten in Furthermore - but even so!) There is a gruesomely fascinating focus on death and the processes involved in ritually dispatching the dead to their otherworld. There are also the spirits of the said departed, who can and do turn particularly nasty at times. But there is also humour, warmth and a good deal of compassion too, so do not worry too much.

Our heroes now have a new and vital mission in this different world. They are slightly older than they were too - very much entering the 'tween' stage of moving from childhood into early adulthood. In this sense, and in some of its themes, this is perhaps a book for slightly older readers than the first, although such matters are highly subjective. To these two familiar figures are added a richly fascinating new character, Laylee. She is also in her early teens, but weighed down by the burden of being the the last (functioning!) descendant in a line of 'mordeshoors'. They are practitioners endowed with the magical abilities to 'process' the corpses of the dead and service their residual spirits. Also most welcome is a new boy character, Benyamin, whose peculiarity is to host myriad insects on his body. Complex and beautifully drawn, both these new protagonists clearly reflect the darker nature of Whichwood, but this does not stop them from being immensely likeable.

Later in the story they are joined by another wonderful character, Benyamin's mother, who, despite 'bad legs' makes a significant contribution to the quest. She is the one to whom the author gives the brilliant line, 'Never, ever again tell a woman she's not strong enough.' A dictum many men would do well to take to heart. On setting off for the city, she is also the one to ready her younger charges with: 'Everyone's got their coats? You've all used the toilet? No? Well, best hold it in.' An injunction many children would do equally well to take to heart. It is great to see an older character contributing experience and common sense alongside the spunk and verve of younger heroes.

Sumptuous language

Tahereh Mafi's remarkable use of language is also just as fully in evidence here. In

Whichwood it is perhaps not quite as linguistically idiosyncratic as in the earlier book, but it is still just as lushly communicative, sometimes thrillingly surprising, sometimes touchingly beautiful. More than anything it is sumptuous, replete with colour. Compellingly

images, which linger long in the mind's eye, are strewn like petals across the surface of the story: the magical red rose bushes that carpet the cemetery; the pomegranate seeds raining red from the sky at Yalda; Laylee ritually bathing herself in the red water. (How many of them are red!)

Her imagery is so often strong and original: 'A skin of darkness had been hitched across the daylight and left to rot until midnight itself had become a curtain of charred flesh you could pinch between two fingers.' (p 35)

Another outstanding feature of this author's writing is her willingness to expand on a moment of time, rather than continually rush into a action. It is not that her story lacks incident or excitement, it has plenty. But her courage to linger in observation and reflection means that she not only can paint wonderful pictures, but also fully explore her characters thoughts and feelings. She gives her readers real opportunity to get to know them intimately, to share their inner lives as well as their external ones. At such times she is never tedious or dull. Quite the contrary; the insights she provides continually captivate and enthrall.

The interjected comments of the narrator continue and indeed grow in frequency too. She (?) even begins to assert an actual relationship to the characters whose story she is telling, adding layers of intrigue as well as narrative complexity. Exactly whose voice is this? And will we ever find out?

I admit to virtually no knowledge of Iranian culture or folklore. (Except for a deep love of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam - and even there I rather think that the FitzGerald translation may have little of the authentic 'Persian' about it.) But I suspect that this author's heritage may have had some influence on both her language and on the character and colours of Whichwood, bright and dark alike. If so, such influence is most welcome. Indeed, whatever the author's inspiration, it could not be more rich or enriching. Tahereh Mafi's writing and her worlds are sumptuous and sensuous in the glorious extreme.

A rose is a rose - or not

The story is as rich in themes and ideas as it is in language. Fantasy it may be, but I know of few better works for expressing the mysteries of that strange, confusing, conflicting 'tween' time of early adolescence. And certainly none better at articulating the grim, uncomprehending pangs of 'first love', as explored here thorough smitten Oliver. Similarly, in Laylee, she explores the difficulty that circumstance-damaged individuals have in accepting help and friendship, convincing themselves that they do not deserve it. Instead they often protect themselves with anger and resentment. Alice's 'task' shows how difficult it is truly to help the likes of Laylee. It also shows how much such individuals need to be helped. To stay true to who you are, regardless of what the world thinks, may be fine and noble. But we all need to know that we are accepted by others if we are to be fully ourselves.

If anyone has doubts that fantasy can be just as much much about human life as can gritty realism, then this is a perfect book to dispel them. Here the fantasy is symbol and metaphor; it is not reality but it is truth.

Through the chapters of Furthermore floats and twirls a ribbon. Those of Whichwood are embellished with a twining rose. (I can only see it as red even though the actual image is greyscale.) It is 'simultaneously beautiful and disturbing'. Like the plate patterns of Garner's The Owl Service, which can be either owls or flowers, or the classic optical illusion, which can be either young woman or old crone, the rose encapsulates a paradox. It is briar and bloom; it is blood and death; it is love and life. And, like Schrödinger's cat, it is an ambiguity which resolves itself only in the eye of the observer. This is a magical story and will make you see the image quite differently at different times. But fear not, dear reader, like Garner before her, this narrator leads us all to good things in the end . 'The wound is the place where the light enters you.'

No ambiguity here

I loved Furthermore, I love Whichwood even more. In my view it earns itself a place amongst the very finest of contemporary children's fantasies. It can also hold its own with some of the greats of the past. Following its US release, the Puffin imprint published a paperback of Furthermore in the UK. I sincerely hope they do the same with Whichwood. These books need to become equally well known to readers over here, and indeed to children worldwide. Those who miss them will most certainly miss out.