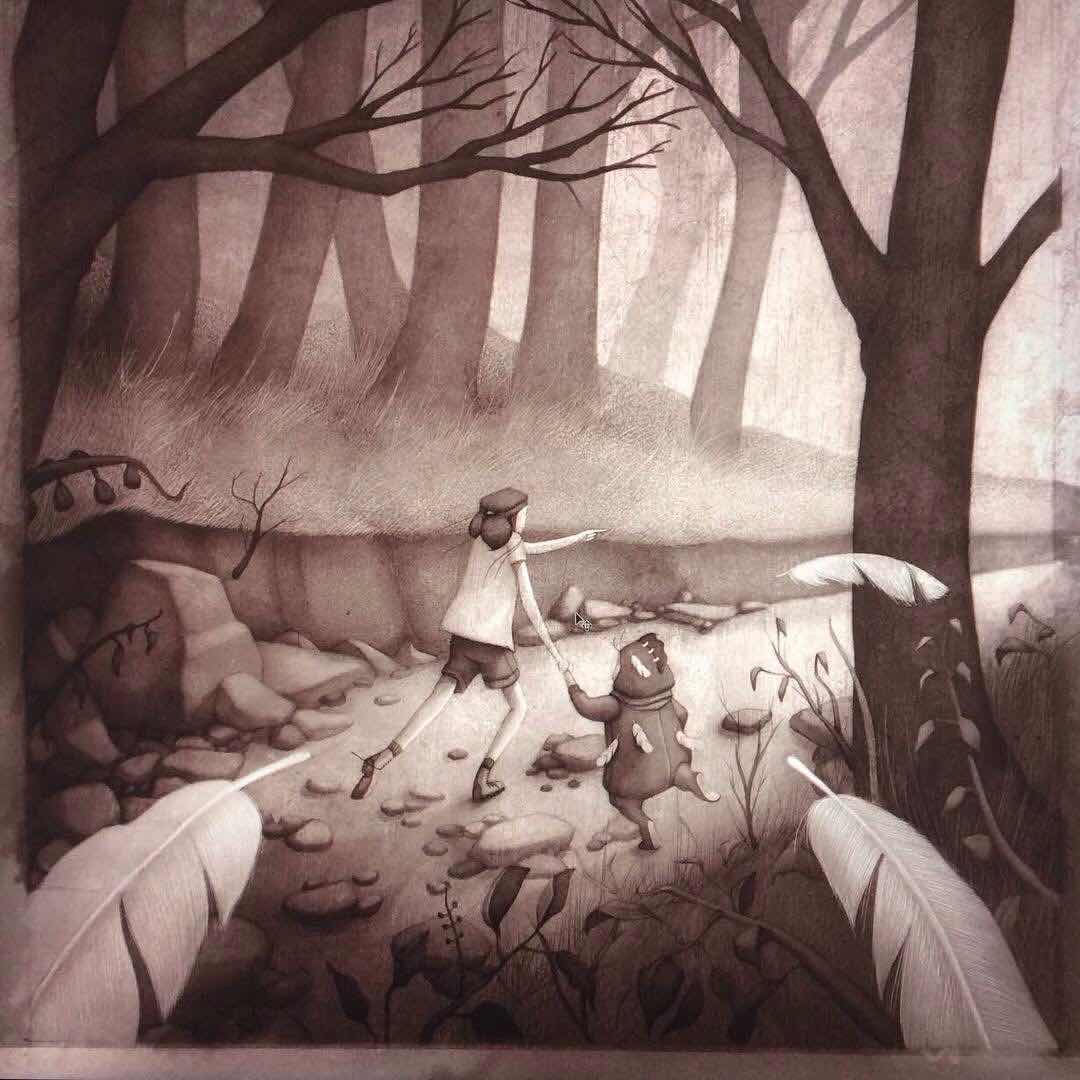

Illustration: Keith Robinson

‘ . . . a fox appears - out of nowhere. . . Wild, wary eyes. Eyes like the ones I see in the mirror when I’m alone. Like the wild worry in me made real, there on the pavement.’ (p 46)

Set for more success

Smugglers’ Fox is the new addition to the outstanding set of MG books by Susanna Bailey. This is very much a set rather than a sequence, as each title is a stand-alone novel. However all are strongly related by both writing quality and by thematic content, each one sensitively combining an exploration of a child’s very real issues and an emotional bond with particular animals. The publishers have also done a commendable job of making the appearance of the books match, through design of the covers, each attractively illustrated by Keith Robinson. On top of the rich engagement of the stories themselves, this is exactly the sort of thing that encourages children to read the full set, which, in this case, would be an excellent thing.

Authentic places

Another compelling feature of Susanna Bailey’s books, is that each one vividly evokes a particular place . This latest is set on the North Yorkshire coast, and the earlier titles on Exmoor, a remote Scottish island and in the Yorkshire Dales.

I happen to know the locations of Smugglers’ Fox well, having spent many holidays in the area, with our own children and, more recently, our grandchildren. I admit, my love for these places added another frisson of pleasure to my reading. However such personal knowledge is in no way necessary for complete enjoyment. This author conjures each scene magically, through imagery and telling detail, yet without resorting to extensive descriptions. She takes us to Robin Hood’s Bay in a way that enables us to hear and smell the sea, to feel the slippery, wet cobbles under our feet, and to experience for ourselves the huddled houses that cling precariously to their steep drop towards the tiny harbour.

Authentic voice

The story of Smugglers’ Fox is about, and told by, Jonah, an almost-eleven-year-old year old boy, whose seriously neglectful mother abandons him and his little brother to the care system. Jonah, understandably, still loves his mother deeply and dreams of her return. When he is also split from his brother, who he not only adores but also feels responsible for, he is devastated. This is compounded by being sent to a small fishing village, especially as he has a pathological fear of the sea. Too frequently he loses himself to bouts of uncontrollable ‘red-scribble’ anger.

Jonah’s voice is caught to perfection, and often we, as readers, find ourselves sharing his emotional desolation. Susanna Bailey’s prose is not complex or poetic, or even particularly lyrical, but she has a way of choosing exactly the right words and images to convey his thoughts both tellingly and affectingly. Her narration captures Jonah’s feelings vividly, with real authenticity, and it makes her relatively simple, accessible language utterly compelling.

‘I’m supposed to tell her how I’m feeling . . . Talk through my worries. Which I can’t, because they’re too big to fit into my mouth, too sharp to fit into words.’ (p 52-3)

Two catalysts play a key role in moving Jonah’s story (and his personal development) forward. One is his new friendship, with a local boy, Freddie, who seems to have problems of his own, even though he tries to keep them hidden. The second is the occasional appearance of a furtive fox, the Smugglers’ Fox of the title, with whom Jonah starts to feel a strong, almost metaphysical connection. These relationships too Susanna Bailey handles with a gossamer touch that makes each, in different ways, seem quite magical. Both Freddie and the fox come to glow warm in this reader’s imagination, just as they do in Jonah’s.

Who cares?

This may be fiction, with some some scenes with the fox even edging towards magical realism, but more than anything it is truthful. The young characters feel real because they show behaviours and reactions of real children. At times it is heart-rending, but Susanna Bailey knows how to begin to heal what she breaks. In Smugglers’ Fox she demonstrates remarkable understanding of the thoughts and feelings of a child torn from his family and placed into ‘care’. Through her sensitive, involving story, she helps us to understand and empathise too. Jonah, like so many children, has to learn to cope with a sadly underfunded care system, and for a long time pushes against it, wanting instead the chance to bring his own sundered little family back together.

‘Too many people have lied to me. It’s like having bits chipped out of your bones and if they do it too much more, you might crumble into dust.’ (p 148)

However he is rescued by individuals who genuinely care (as many do, or try to) - although his own concern for others plays a huge part too, as does his identification with the brave, almost magical, fox. Adults as well as children could learn much from this affecting story about how to heal emotional wounds, and, thankfully, some will. That makes it an important addition to the children’s literature canon, as well as a most engaging, if sometimes emotionally challenging read.

It is particularly to Susanna Bailey’s credit that she unobtrusively includes here the possibility of adoption by a same sex couple. This is treated exactly as it should be in a book for children, not as anything remarkable, but unquestioningly as an arrangement that can provide a loving family, just like any other. Such are the little ways in which we can help our children grow into members of a more inclusive society.

More than

Anyone seeing the covers of Susanna Bailey’s books (attractive as they are) and thinking these are ‘just’ animal stories needs to look far more closely. They are this, but much more too. Were I still teaching Primary I would most certainly want to see them all on my classroom shelves and would recommend them warmly. They are books accessible for independent enjoyment by most reasonably confident readers, as well as excellent potential novels for reading aloud. Beautifully written, they offer riches of thoughtful content and will do much to stimulate reflection and discussion at the same time as providing absorbing reading pleasure. This latest addition to the set is every bit as special as the others.