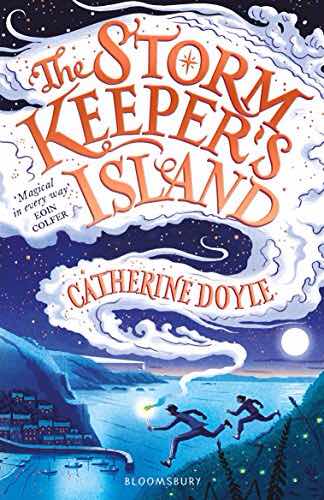

Cover illustration Bill Brag, lettering Patrick Knowles

'. . . places can be just as important as people. . . they can have the same power over you if you let them.' (p 4)

Quotable notable

Sometimes a book offers up so many delectable quotes that I agonise long over which to include. It is often a sign that it is a great book. The Storm Keeper's Island does. And it is. Occasionally, but only very rarely, I come across a book that I just know is one that deserves to join the canon of 'classic' children's literature. This is such a book. However, thoughts of potential status should not distract from the fact that it is is a totally gripping read, and ultimately a very affecting one.

This is a story firmly grounded in an actual and particular place, the wildly beautiful island of Arranmore (Árrain Mhór) off the northwest coast of Ireland. Catherine Doyle, herself rooted in the place and its myths, develops a story of an evil Sorcerer, Morrigan, buried deep in the island, which is now protected by the mysterious and elusive 'gifts' of her benevolent counterpart, Dagda. At the same time, the human role of 'Storm Keeper' is being passed through generations. The holders do not only embody those 'gifts', in some strange way, but have, over time, captured particular instances of weather, in the form of numerous wax candles. In these candles are held all the layers of time that have built up the island's climate, its character and history. For example the author writes of one such candle:

'It was sheets of freezing rain and the burnt shriek of lightning striking sea. It was peril and adventure and terror and hope all rolled together, and it was unapologetically pungent. ' (p 159)

It is all wonderfully imaginative, yet completely credible in its own context, and hence enormously potent.

Layers of time and meaning

This book has much in common with those of Alan Garner and Susan Cooper, in that it unpacks the strata of time encapsulated in a particular place. In this case its remote, wild island embraces sea as much as land, weather and sky as much as earth and history. However, for all its depth, its layers of magic and myth, time and place, The Storm Keeper's Island, is not obscure or inaccessible. It is also wildly, stormily exciting and completely enthralling.

The magic here is rendered all the more credible (or incredible) by its juxtaposition with vividly drawn contemporary characters, centring on rival siblings Fionn and Tara. They are completely convincing, often in conflict with each other, or even themselves, and yet the layers of myth are as much acted out in these children as they are in their island location. Fionn and his sister must work through the inherited battles of previous generations, enmities and loyalties, the ambitions of contemporary islanders, and the traumas and tragedies of their own family. Reality and magic become the mirrors and metaphors of each other, each 'storm', and each magic candle. both the externalisation and the internalisation of conflict and resolution that is richly resonant. In this, The Storm Keeper's Island reminds me of Alan Garner's The Owl Service, although Catherine Doyle's book is less obscure, more accessible to young readers, whilst ceding nothing in depth of mystery or magic.

What is it about the Irish?

I don't quite know what it is with Irish writers and the creation of wondrous poetry and prose in English, but there just has to be something. Aside from all the long and fine legacy of Irish writing in the past, we have relatively recently had children's fantasy writing of staggering brilliance from Dave Rudden, as well as from Matt Griffin and the late, and much missed, Nigel McDowell. All distinguished by breathtaking language.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise then that one of the many remarkable features of Catherine Doyle's stunning writing is her use of language. Hers is language that digs into meaning much deeper than the words she spreads over the page. It delves below the surface of characters and locale, island, cottage, sea and chimney smoke. But what we discover in its depths is not simple or blatant. Its secrets are hinted at. rather than laid bare, revealed by inference, rather than exposition. Its power is not in exuberance on elaboration but in the superbly chosen word, original, surprising in its context. She creates images that illuminate, sometimes with a flicker of candlelight sometimes with the electric brilliance of lightning.

'(Fionn) wanted his father to be unchained from the lifeboat at the bottom of the sea. . . All his life it had dwelt in the sliver between his soul and his heart - where desire dissolved into impossibly.' (p 43)

No more sandwiches

The Storm Keeper's Island has already been called Book of the Month, and this time those who have tagged it have got it so right. But it is and will be more too. It could well be a Book of the Year, of the decade, and on. Catherine Doyle's is one of the most devastatingly exciting new voices in children's fiction that I have encountered in a long time.

As the story has promised all along, this book turns out to share a major theme with so many other children's fantasies: an ordinary boy who is chosen as the special one to lead the defence of his world against the powers of darkness. It is the narrative of his coming into power.

'Being a guardian of this wild and ancient place would mean learning snowstorms instead of long division, composing rainbows instead of acrostics.' (p 147)

Yet Fionn is not quite a Harry Potter or a Percy Jackson. He is far more. His story is deeper, richer and more genuinely dark. It is linked to the power of an island, to the power of the elements, both to place and to the resonance that lies within us all as human beings. His story is a great fantasy, and is surely the opener of an even greater fantasy sequence. Its completion looks set to be one of the children's book events of the (hopefully) not-too-distant future.

For much of the book, Fionn is afraid of the sea and its storms. He does not believe he has the courage to take up the challenge the island offers him.

'He was not brave . . . When everyone else was in Helm's Deep, he'd be back in the Shire, making a sandwich.' (p 45)

But on Arranmore he finds a new self as well as an old self, an ancient self, yet still an entirely contemporary self,

Even into the storm. . . Especially into the storm. 'You just have to walk . . . Will you walk with me?'

It is an invitation from his grandfather to Fionn. It is also an invitation from Catherine Doyle to every potential reader.

Leave off making sandwiches and accept it.