'Perhaps it was just as important to be still - to listen keenly - and to see into the heart of the things that most people missed.' (page 95)

Coming late to the party

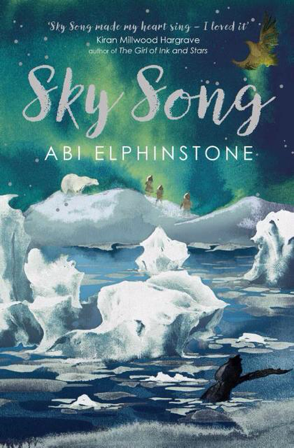

Yes. I know. I am way behind the crowd on this one. Sky Song has been piled high in bookshops for weeks now, lauded and recommended all over the place.

After delighting in the author's previous The Dreamsnatcher trilogy (see my posts from March '16 and June '17) I was not in the least surprised at this enthusiastic reception for her latest release. And now that I have read it I can only (belatedly) add my voice of recommendation to so many others. In doing so I feel rather like the sad sort who ends up feebly sending a 'Sorry I missed your Birthdaty' card. Yet I can't neglect recording my own thoughts on such a significant release, however tardy. Rather than simply repeat all the plaudits about this being an enchanting story both for children to read themselves and for teachers to read to them (which it is), I would like rather to try to explain why I think this little gem is so much more than just a good story. Abi Elphinstone is a writer of great sensitivity and because of this offers much that will help sensitise her young readers to some crucial aspects of both literature and life.

Difference is good

Sky Song is most wonderfully strong on celebrating diversity and inclusion. One of its trio of protagonists is Blu, a girl with characteristics that, in the terms of our own world, suggest Down Syndrome. It is both inspired and inspiring to see such a girl feature so prominently in a mainstream book. There are, it's true, a good number of recent children's books about individuals who are 'different' in some way. Some personalities especially, such as children on the autistic spectrum and those with specific reading issues, have featured relatively prominently. This is certainly an excellent thing But in all my extensive reading, I don't think I have come across DS in much mainstream children's fiction, so Blue is particularly welcome. That she is not turned into an 'issue' but treated as an accepted lead character in her own right, contributing significantly to the success of the book's quest, makes it even better. It is really important for all children to be able to find themselves in the books they read or hear, but it is equally important that all children are sensitised to the idea that 'difference is good' when it comes to those around them. This book will help enormously.

Stereotypes are bad

Additionally Eska, the story's lead character, provides a wonderful role model for the 'rebel girl'. It takes her no time at all to show that she is no mere 'rescued princess', despite her being liberated from the snow queen's Winterfang Palace - by a boy! She is everything a strong, gutsy, determined, resourceful protagonist should be, including being enormously likeable. Yet there are quite a few strong girl leads to be found in recent children's fantasy fiction. And a mightily good thing it is too. About time. However, even more remarkable (and laudable) for me is the almost equally prominent presence in Sky Song of Flint, a sensitive and sensitively drawn boy character. Feminism brings crucial understanding of girls' rights and potentialities to our society and is justifiably prominent. But it is perhaps easy to forget that boys too can be constrained and sometimes even crushed by a gender stereotype imposed and reinforced by society. Some boys also need to be encouraged and supported to be 'rebels' if they are to break free from the pressure to conform as 'real lads'. Some need to find themselves in other ways than as noisy, aggressive, sport-loving 'warriors'. That Flint is presented as a caring, empathetic and inventive believer in magic is enormously helpful.

'I'm not sure I'm going to make a very good warrior though. Too much - ' (Flint) looked at Blu, searching for the right word, '- gentleness.'

'I don't think you have to fight with weapons to be a warrior,' Eska whispered. 'You can fight with love and tears and inventions instead.'

There are different ways of being a rebel and, if our society is to become a better place for everyone, we need to learn to respect them all. Of course I know that there are some sections of our society who understand this already. But, sadly, there are also all too many who do not. A book like this can help, perhaps more than laws or lectures. Flint is is just as important a role model to find in mainstream fiction as are Eska and Blue. We owe Abi Elphinstone enormous respect and gratitude for putting all three in there.

'If hope was a song it would sound just like this.'

The magic of 'the wild'

Perhaps because of her personal experience, through her upbringing and later travels, this author is also enormously responsive to landscape. Through her, her characters show the same sensitivity to place and to the abundance of nature it supports. In Sky Song, close relationships with animals figure strongly and are most tellingly and touchingly portrayed.

'I don't belong to a tribe - I don't really know where I fit in exactly - but if my tribe ends up just being you and me, Balapan, that would be enough.' (Eska to her eagle)

Of course, such human/animal closeness is not uncommon in children's fiction, but Abi Elphinstone goes further. It is the sense of her protagonists' empathy with nature as a whole, with 'the wild', which is so beautifully captured.

'As Flint glanced at Eska he felt a strange tingling fill his body. She was surrounded by the wild - her tribe - and for a moment it felt like the animals were singing just for her.'

Even the 'magic of Erkenwald', forgotten by so many but kept alive by Flint and a few others, is the magic of nature, of the earth itself.

'Flint still trusted Erkenwald's magic . . . because his mind was attuned to the things most people missed - river stones that shone in the dark, sunbeams tucked behind trees, coils of mist hovering above puddles.'

In their wonderful book of art and poetry, The Lost Words (see my post from October '17) Jackie Morris and Robert Macfarlane conjure 'spells' to put young readers more in touch with the natural world. Here, albeit through a different genre, Abi Elphinstone does very much the same. And although the location of her tale is probably not that of most of her readers, sensitivity to nature is transferable. Through this strong and moving story I believe many children will become more sympathetic to the whole notion of 'the wild', whether it is far across the world or in their own backyard. And in fact both are vital.

A door into fantasy

In an earlier post, I welcomed The Dreamsnatcher trilogy as 'entry level' fantasy for young readers. I do not see this as a pejorative description in any way. Quite the reverse. High fantasy abounds for somewhat older readers, (YA and beyond) but it is always good to have books that introduce such stories to children in an accessible and exciting way. Recently these seem to have been rather thin on the ground, here at least, if less so in The States. Fantasy is an important genre. Just as much as 'real life' books, fantasies help us discover more about who we are; about what other people do, think and feel; about the world in which we live. It is not just 'pretending', it is imagining. Like much of poetry, fairy tale and fantasy explore life through images, through symbol and metaphor; and, at its best, it can plumb deeper than perceived 'reality'. It resonates, sometimes unconsciously, with the depths of what we human beings are and always have been. It points to the universal in all of us. And Sky Song is an even richer imaginative fantasy than Abi Elphinstone's earlier books. It resonates in exactly this way. It is replete with many of the classic tropes of fantasy: the rescued prisoner; the divided kingdom; the wise magician who shape-shifts; the wicked queen or witch who steals voices (identities, souls, daemons?); the warrior who scorns magic; the hero journeying to complete the quest that will end evil. It is not necessary for a young reader to understand all or even any of these, just to get to know them is enough. A book like this will help children remember and internalise these archetypes, so that they will later be able to appreciate classics like Susan Cooper's The Dark is Rising and new wonders such as Philip Pullman's La Belle Sauvage. It is a magical doorway into a magical world in more ways than one.

Language that speaks - and teaches

There is one further sensitivity in Sky Song that I think important to mention, and that is Abi Elphinstone's profound sensitivity to written language. It is not that her usage is 'fancy', quite the reverse. It is communicative without being ostentatious, descriptive without being florid. It clearly moves the story, builds the characters, creates and releases tension as appropriate for such an adventure. But it is just the sort of writing that familiarises children with the power and potency of the written word. And it does not always need cumbersome disection by a teacher, or even conscious awareness on the part of the reader, for such quality language use to be absorbed. The young are sensitised to the apt choice of word, the nice turn of phrase, the elegant balance of a sentence by encountering these things frequently in their reading. Writing is, at heart, learned from reading, and the simple but telling use of language is best learned from the models unobtrusively provided by skilled authors such as this.

A wonderful example is the passage about flying the 'Woodbird' on page 243.

Want the good news or the good news?

Sky Song is a hugely engaging story beautifully told, and the many sensitivities enmeshed in its telling make it a major addition to the canon of contemporary children's fiction. Wrapped within its fantasy is a book of tremendous heart. No. Not just heart, humanity.

I have picked up from Twitter than Abi Elphinstone has been commissioned by her publisher Simon & Schuster to write a new fantasy series, which she is currently calling The Unmapped Chronicles. This is brilliant news. I will await it eagerly. I also know that huge numbers of other readers will be doing the same. Which is equally excellent.

One final thought. As someone who values and treasures books in the long term I think it is sad that often these days UK publishers do not produce a hardback edition alongside the more ephemeral paperback. Having said that, this edition of Sky Song is one of the best designed and presented children's paperbacks I have come across in a good while. It too will help sensitise children, this time to both the look and the hand-feel of beautiful books. Perhaps we will soon get a US-published hardback to go alongside it. I do hope so.