The best of the best

Here are the titles that made the most outstanding impression on me in 2019. They confirm, yet again, the breathtaking quality of literature currently available for readers between about 9 and14.

First class sequels

This year has seen the arrival of a number of follow-ups to books that I hugely enjoyed. To be honest, sequels can sometimes be a bit of a let down, especially when they have been eagerly awaited, but not so any of these. Every jot of anticipation was delightfully fulfilled, and even exceeded.

Piers Torday is developing as a very special link between children’s classics and the best of contemporary writing. Together with others such as Michael Morpurgo and Cressida Cowell, he does much of enormous value to promote children’s reading, both within and beyond his books. He would, in fact, be my nomination for the next Children’s Laureate. His homage to C.S.Lewis, The Lost Magician (review Aug ‘18), was far more than mere pastiche, a fine work of fantasy in its own right. Now its sequel, The Frozen Sea, lives up to that auspicious start quite wonderfully. It is magical, in every sense, and a book-lovers delight.

The Train to Impossible Places by P.G.Bell (review Nov ‘18) was one of the best examples of children’s entertainment reading that I have come across in a long time. Its sequel, The Great Brian Robbery is no less so. It has just about everything: humour, excitement, wild imagination, delightful characters - and trains. It is a real portmanteau of everything children will love in a zany, escapist fantasy.

Catherine Doyle’s The Storm Keeper’s Island (review July ‘18) is a children’s fantasy that stands in a line of succession stretching back to the likes of Alan Garner and Susan Cooper - and it is a totally worthy successor to those illustrious predecessors. The recent sequel, The Lost Tide Warriors retains, and indeed exceeds, all the same wondrous qualities. It has a rootedness in place and the grounding resonances of traditional story and myth, whilst still adding new layers of wonderfully fecund imagination. This is a developing sequence of exceptional quality.

I found The Shadow Cipher, the first volume in Laura Ruby’s York sequence (review Jan ‘18) to be an astonishing delight in so many ways.This quirky mystery adventure is a totally intriguing read, brought alive by a quite devastatingly entertaining, and diverse, cast of characters, not least its young protagonists. The sequel, York: The Clockwork Ghost now continues and extends the saga with huge originality and breathtaking writerly skill. UK readers should not be put off by the US cultural context of this series; its pervasive humanity and its compelling narrative involvement are universal.

Stand out stand-alones

Much as I love sequels, sequences and sets, my most outstanding reads of all this year happen to have been stand-alone stories. They are also, in their various ways, very challenging books. None of them are easy reads: some are difficult to handle emotionally; some involve difficult themes and ideas; some are difficult structurally; and some are all of these. They are, in fact, superb examples of when children’s books become children’s literature. It is, of course, important for young readers to have access to books that provide amusement, entertainment and diversion. It is equally important, though, that they experience books which take them further; books which can help them grow as people and as citizens of the world; books which can perhaps encourage and support them in making that world a better place.

Donna Harraway, in her introduction to the brilliant The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K Le Guin (published by Ignota, 2019) says: ‘Storytelling might well be fundamental to organising and promoting cooperation in human evolution.’

These books contain storytelling of exactly that mind-expanding, life-enhancing, humanity-evolving kind. It is no good expecting them to be easy.

Christopher Edge has recently written a number of brilliant children’s books using engaging story to explore some of the most difficult concepts of recent physics. Now with The Longest Night of Charlie Noon (review May ‘19) he has produced a gripping, puzzling, surprising novel which approaches metaphysics in its exploration of time itself. It is a book for those who want children to think big thoughts, and live big lives. It says to us all: You can’t stop what’s coming, but you can help to shape it into something better. . . . The actions you take will change the world.’ (p 170/171)

Chloe Daykin is an author who tells wonderful, and important stories, often making accessible to young readers sophisticated narrative forms more usually associated with adult fiction. In doing so she offers up to them early glimpses of the rich possibilities that fiction has to offer. Fire Girl, Forest Boy (review July ‘19) introduces a version of magical realism as a way of exploring both environmental and character issues. It is a book that expands experience and engenders empathy, yet it succeeds in being an engrossing adventure at the same time. Her writing is a joy. Her rich gifts to children are invaluable, and given without any hint of patronising.

Rarely have I encountered a children’s book that deals so sensitively with illness and loss of a much-loved sibling as Karen Foxlee’s Lenny’s Book of Everything (review March ‘19). One of Australia’s leading contemporary children’s authors, she had written other outstanding books too. This one actually came out in Australia last year, but since it was only published here (in paperback) this year, I feel justified in including it. Its very moving story involves a young girl living alongside a brother with the unusual condition of gigantism. However the book’s profound understanding and acceptance easily translate into sensitivity towards all who are unavoidably different. It, therefore, has much to say to all children. It is harrowing, but equally charming, amusing and beautiful - and not to be missed.

Anne Ursu is one of my favourite US children’s authors, and, I think, one of the greatest, Her book The Lost Girl (review March ‘19) introduces twin girl characters, almost identical in looks but very different in who they are, in a story that encompasses both the real and the fantastic. It explores in depth questions of identity, of truth and illusion, of individuality and of group solidarity. It is a deeply feminist book, but it is far more too. It is not a comfortable book. It is one to read and then return to. It is full of enigmatic images. Its story, like life, holds some of its secrets close, to be pondered, to be teased at, even to worm their way into a reader’s dreams. This is a novel that is both riveting and revelatory, from a writer of breathtaking skill and imagination.

Nicole Melleby’s Hurricane Season (review June ‘19) treats bravely with two subjects that have too long been taboo in children’s fiction, mental illness and same-sex relationships. It deals with them openly and honestly, yet it also deals with them with great sensitivity, in a way that to me seems totally appropriate for young readers. It also explores the life and experience of a child thrust into the role of carer, a situation that some readers will know well, and others need to understand better. Those who have experienced something similar to the life this author so touchingly evokes will find comfort and hope in seeing themselves here. Those who don’t will learn much. It is a story brim full of life, music, art, love, sadness, beauty - and humanity.

Although Frances Hardinge began her rightly acclaimed writing career with delightfully quirky fantasies, she has more recently turned to deep, dark fiction with a quasi-historical setting. Now she returns to fantasy with Deeplight (review Dec ‘19). However, here she conjures a world from her wildly idiosyncratic imagination with much of the same depth and complexity as in its award-winning predecessors. This is a novel of rich ideas and multiple themes. It challenges and confronts, as well as entertaining magnificently. More than anything, though, it is a story about the power and potential of stories: stories true and untrue; stories invented and inherited; stories believed and doubted; stories that save and stories that kill. It says that stories are what we are, and make us what we are. And it is not wrong.

My Book of the Year

In previous years, I have not singled out an overall favourite, but this time one novel made such an outstanding impression on me that it begs for this title.

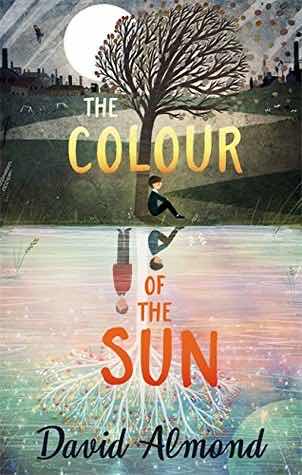

Cover: David Litchfield

Last summer, I read right through all the principal novels of David Almond in writing order, and I have to say it was one of my finest reading experiences ever. There is so much more to this author that Skellig, remarkable book though it is, and in my view he ranks with the likes of Alan Garner and Ursula Le Guin as the truly great writers of (children’s) fiction in English. His latest novel The Colour of the Sun (review Aug ‘19) is the quintessence of his writing, with a theme he returns to often, that of the relationship between identity and place. This short novel’s superficially simple writing belies layers of richly resonant imagery and meaning. It explores a lifetime of experience and growth through one day’s there-and-back-again ramble. It is quite simply a masterpiece.

And now . . . My Publisher of the Year

I have never before nominated a Publisher of the Year, but feel the need to do so now. Children’s titles created by BAME writers and books with lead BAME characters are becoming just slightly more in evidence - but still far too slowly. What Knights Of are so strongly contributing in this is therefore warmly to be welcomed and should be supported with conviction. Their work to place into the mainstream of UK children’s publishing outstanding writers like Jason Reynolds (see my review of Ghost, June ‘18) and popular adventures like The High Rise Mystery by Sharna Jackson (review April ‘19) is a wonderful thing. These fine books are of inestimable importance both for children who are of BAM ethnicity and for those who aren’t. They provide high quality reading experience with vital implicit messages about the value of all individuals within our wonderful, diverse society and need proudly to be present on classroom shelves in every school in the country. We who are passionate about children’s reading should shout out, at every opportunity, for Knights Of, and for all writers and publishers who are providing children with positive images of diversity and inclusion.