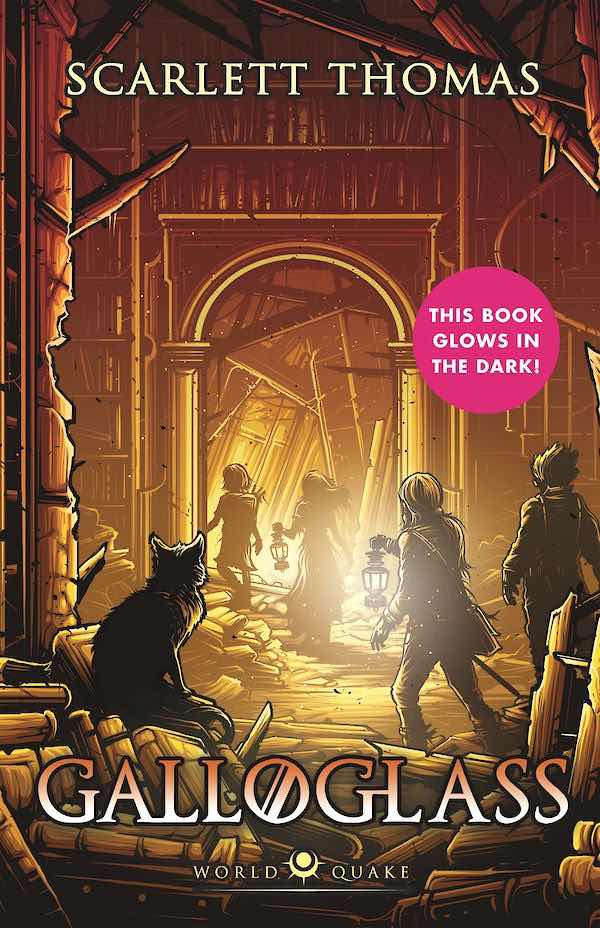

Cover: Dan Mumford

‘Applying stories to life - or vice versa - is one of the things we’re best at. It can go too far of course. But that’s never stopped me.’ (p 295)

A quiz

Books in Scarlett Thomas’ Worldquake series have the distinct advantage of being easily locatable in the dark. Switch off the bedside light (after the lengthy bedtime read that they inevitably provoke) and once it’s gone (the light that is) they will spontaneously emit Luminiferous Ether (well, something like that).

Another distinguishing feature of these novels is their ability rapidly to identify the age and character (kharakter?) of any reader (by means of a quick and entertaining quiz). Viz:

Did you think Galloglass was:

A) a brilliant fantasy adventure about five children with magical talents; the best thing since a Harry Potter?

B) a highly entertaining pastiche of just about every children’s fantasy novel ever written, underpinned by brilliantly wicked satirical sideswipes at contemporary society?

C) a witty amalgam of creatively reimagined fantasy tropes and scenarios giving them vital new resonance in a post-modern age?

If your answer is:

Mostly A: You are a child of around 9-12; never stop reading

Mostly B: You are a Senior Citizen who has spent a lifetime reading far too many children’s books; no point in stopping now

Mostly C: You are a professor of English who is possibly too clever(and too talented)by half: never stop writing

No kidding

Joking apart, the correct answer is actually ‘all of the above’, which could easily have ended up as “a bit of a pile-up”. But not here. Scarlett Thomas proves that it is possible to take many well-used elements from much-loved children’s fiction and, by bringing to them both writerly skill (not least in narrative construction), rich imagination, and no little wit, remould them into something original, and joyous. And the most remarkable thing is perhaps, that, by and through all her cleverness, she successfully tells a story for children that is completely compelling, and, well . . . quite magical. Galloglass, will be much enjoyed by adults who like reading children’s books, too, but that is something different. It has many elements of sophistication, but then many children are remarkably sophisticated readers. It is still a essentially a children’s book. However, there is absolutely nothing demeaning about saying this. To write such books well, requires exceptional skill, and their potential influence is staggering. ‘Every new book makes a much bigger difference to a child than it does to an experienced adult reader.’* Scarlett Thomas’ Worldquake novels will be enjoyed by many, on any number of levels, depending on the experience and sensibilities of each reader. They will, however, glow hauntingly in the memories of all.

Best yet

It can be the case, with series fiction, that inspiration becomes thin and ideas over-stretched once the energy of the initial volumes has dwindled. That is emphatically not the case here. If fact, quite the opposite, the first two titles in the Worldquake series were fine books; Galloglass is a truly great one - strange, quirky, complex, challenging and, yes, truly great.

I love that Scarlett Thomas, skilled and experienced writer of high quality literacy fiction that she is, does not condescend to her young audience, as can many of the popular children’s books currently piled high in bookshops. At present, the (over?) simple viewpoint of first person, present tense narrative, seems to be ubiquitous. I know this makes for easy reading, and children do sometimes need the security of easy comfort. But literature should challenge as well as merely entertain, and I think children’s literature is no exception.

Scarlett Thomas weaves her narrative from multiple strands and perspectives including those of different members of the story’s group of magical children, several (potential) perpetrators of unspeakable evil - and, indeed, a cat. Amongst her many other writerly skills, she is a true expert in plot construction. She understands exactly how to bring readers with her every step along the convoluted path of her narrative, and hold them enthralled. She knows just how to lull with candy floss and pretty flowers before suddenly throwing a vicious punch to the emotional guts. She knows how to intrigue and tease with story lines suddenly, if temporarily, dropped, only to pick up another exciting thread. And then, just as Galloglass is developing beautifully, along the lines that you might expect of the sequel to its two predecessors, the author catapults her reader into worlds that are, even in this context, truly bizarre, with storylines, by turns, intellectually challenging and emotionally disturbing.

Not only does the author pick up on imaginative worldscapes from her previous books - the wonderfully named Tusitala School for the Gifted, Troubled and Strange in the ‘Realworld’ and Dragon’s Green with its Awesome Great Library in the ‘Otherworld’ - but readers will also find themselves amidst a futuristic variant of the Hunger Games scenario, where combat is by ethical questionnaire rather than armed conflict, and even a surreal world of

cats, served by butlers and drinking ‘pawsecco’ and listening to jazz in a cellar, that conjures the paintings of Louis Wain.

‘“That,” said Marcel, “is the local cats’ home. . . Someone donated a billion pounds to them. Inside the building are the richest cats in the whole world. . . I hear that the chef is in line for the first Michelin star to be given for pet food.”’ (p 108)

There are even ‘personal’ appearances from no less than The Bermuda Triangle and The Northern Lights. That’s not even to mention the odd spacewarp into the world of Douglas Adams (The Luminiferous Ether manifesting as a gigantic stick of pink rock!) To say the whole is a riot of wild and wonderful imagination is almost an understatement.

From satire to ethics

And all of this is peppered with witty authorial sideswipes at many aspects of contemporary life. Her targets can be trendy vegan food, self-help manuals, or ‘survival guides’,

‘His trained warrior’s eyes scanned . . . for landmarks he could use to navigate, for enemies, and for sources of food or materials he could use to construct a shelter. Flowers often pointed south, he’d read once. But of course Wolf didn’t know where he was and therefore in which direction he was supposed to go. And there were no flowers.’ (p 109)

or even, perhaps, contemporary politics,

‘(It was) the subject of many complex negotiations . . . But complex negotiations took a very long time.’ (p 285)

All add amusing leaven to Scarlett Thomas’ fantasy world.

However, what singles this book out for particular greatness is the depth of its thinking, and the depth of thinking it provokes. One of its story strands deals with the very serious issue of child molestation. The abuse is not overtly sexual, but is sufficiently disturbing to heighten children’s awareness about what is inappropriate. The victim’s responses are both sensibly and responsibly dealt with and the resolution will be hugely helpful to children, as well as to adults, many of whom will want to discuss this with their charges.

Beyond this, though, the storyline raises deep moral and philosophical issues, to the extent that it could well be used as a text in ‘ethics for active young minds’ It asks such provocative questions as ‘Is selfishness necessarily always bad thing or altruism invariably a good thing.?’ It treats of Nietzsche and of a concept of ‘flow’ as might be found in, say, Ursula K. Le Guin’s wonderful poetic translation of the Tao Te Ching. Few children’s books come close to this level of intellectual stimulus, but it is so well handled here, so cleverly integrated into the issues and choices faced by its magical protagonists, that it will be a ‘Realworld’ boon for sensitive and thinking young readers. This is another wonderful book for them to grow up with and through.

‘Neptune, like all creatures bound to one universe, one planet or one locality, simply could not visualise the unknown. The unknown is, of course, by definition, not known.’ (p 136)

Galloglass helps to expand the universe we can visualise and so to push back the shadows of intellectual darkness.

US edition

Famous for fun

Although I was already a fan of her adult novels, enjoying some and admiring all, I think her decision to write children’s books has been the making of Scarlett Thomas. She puts these words into the mouth of one of her characters:

‘Lady Tchainsaw was quite famous and had recently joined the university‘s Creative Writing Department. It was always good to get in with the creative writers. Not only were they the most famous members of the university, but everyone knew they had the most fun.’ (p 120).

Well, Professor Thomas, if Galloglass is anything to go by, you might just be correct on this second point, and fully deserve to be so on the first too.

University Library (Special,Collection) Rules: ‘We only have three rules. No chewing gum. No talking. And if you die, it’s your own fault.’ (Galloglass, p 134)

University Library (Special,Collection) Rules: ‘We only have three rules. No chewing gum. No talking. And if you die, it’s your own fault.’ (Galloglass, p 134)

Note:

*Peter Hunt, How Did Long John Silver Loose his Leg? (2013), p 136