The Magic Thief

Were I to list my top ten children's magic fantasy sequences from the 'post-Potter' era, then Sarah Prineas' The Magic Thief books would certainly be up there. They may not be amongst the more profound of such works, but they are certainly amongst the most enjoyable. They have all the qualities of first rate fantasy entertainment.

Now she has struck gold again with The Lost Books. Precisely the same accolades apply, and they apply to this recent offering largely because of two outstanding qualities.

A librarian and a queen

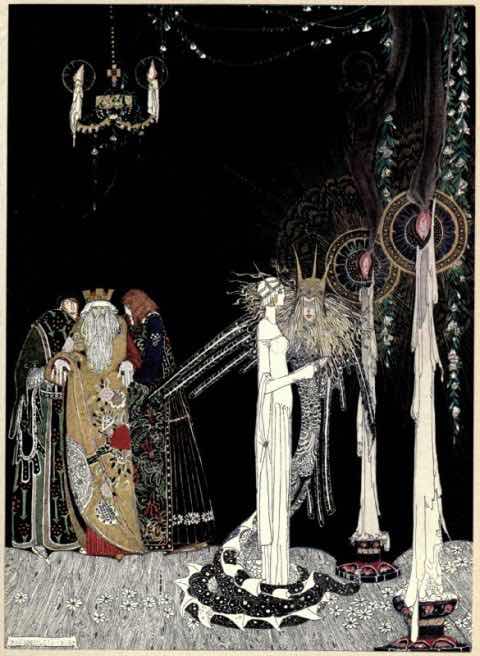

This book shares its core premise with most other children's fantasies; a young boy discovers a special destiny and has to grow his way into it. His dramatic journey is paralleled by that of a young girl. The setting of a broadly 'mediaeval' fantasy kingdom is very familiar too, although no less convincing for that. However Sarah Prineas' most recent take on these tropes is both original and highly imaginative. Young Alex's discovery is not that he is a wizard, but a librarian, albeit one who has to contend with enchanted books, many of them violently hostile to boot. There have been many books about books over the years, but this one is certainly fresh and vivid. It explores, both explicitly and implicitly, the many potentialities of books, their power to be a source of evil and of good.

At the same time, it charts the journey of young queen, Kenneret, from domination by her self-seeking, former regent uncle, to acceptance of her own authority and responsibilities. It is a tale which very successfully marries an exciting and engaging plot with many prompts for thoughtful reflection. And of course any book that celebrates libraries and librarians is, in the present climate, warmly to be welcomed.

Irascibility and bickering

Yet it is not the narrative context that is the real delight of this novel, but its characters and relationships. Alex is far from the usual fantasy hero. Rather he is moody and petulant. Quick to anger, he often opens his mouth inappropriately, when he would do far better to keep it closed. And yet he has a basic honesty of demeanour which is refreshing and his unswerving determination to become a librarian and protect his books is richly admirable. He manages to be hugely engaging despite his many flaws. Similarly his relationship with Kenneret is far from an easy friendship. Their bickering and even outright hostility are frequently entertaining. Witnessing their gradual growth towards grudging mutual respect is possibly the highlight of the novel.

More to come?

Although it appears that Sarah Prineas has a new novel, Dragonfall, in the pipeline for this coming year, it does not look to be a sequel to this. It should, of course, be well worth looking out for in its own right. Yet it would seem from several clues that The Lost Books is being set up as the start of a new sequence. I do hope so; it has much potential to be an outstanding one. However, either way, there is clearly much to look forward to from this excellent children's writer.